From Roslagen's Embrace

From Roslagen’s Embrace #

The lighthouse island Högbonden 1921–1947: The Jansson family’s story from the High Coast.

Slideshow where Elsa and Ulla are interviewed by Björn (the author) about photos and people (in Swedish):

Want to see more photos? Visit the gallery.

↓ Scroll to read the full story ↓

Foreword #

Forsmark Ironworks 1887

Klas Gustav Jansson tends the simple stove to heat water and keep the cold out of the cramped, damp dwelling in the farmhand quarters at Forsmark Ironworks in northern Uppland. The fire crackles and warmth spreads through the room with its smoky, burnt scent. The year is 1887 and Klas’s wife Greta Stina lies in bed ready to give birth. Klas, a farmhand at the ironworks, can barely stand still and doesn’t quite know what to do with himself. Two neighbor women help with the delivery. Greta Stina has strong contractions but everything goes well and it doesn’t become particularly dramatic. Klas breathes a sigh of relief, puts more wood in the stove, sits heavily on the edge of the bed and looks lovingly at his wife and newborn son. The boy Knut Linus Ludvig Jansson would eventually become my beloved grandfather.

Knut went to sea early. Initially as a crew member on cargo ships along the Swedish east coast. After that he worked for a time on a lightship. After a year as a lighthouse assistant at Landsort, Knut and his wife Augusta moved to a similar position at the Lungö lighthouse outside Härnösand. My grandmother Augusta, née Viberg, grew up at Tvingudden in the parish of Börstil. The nearest village was Långalma, not far from Östhammar. Grandmother had a “green thumb” and dreamed of cultivating on a larger scale. It would turn out that this dream would not become reality.

Knut was a man of very firm opinions. Compromising didn’t always feel comfortable to him, and standing with cap in hand begging and pleading was unthinkable to him. “If you can’t eat your fill, you shouldn’t lick yourself full” was an expression he often used. Since grandfather and the lighthouse keeper on Lungön didn’t get along, it was decided that after 7 years at the lighthouse he would swap places with the lighthouse assistant Petrus Öberg on Högbonden. That’s how simply conflicts were resolved in those days. A rocky island in the middle of the sea without a natural harbor, electricity or drinking water off the Nordingrå coast, once called “Devil’s Island” by Sixten Söderblom. There the family moved with three children and a dog on November 28, 1921. My mother Elsa was then one year old. One child, Alfred, who died in infancy, was left behind buried on Lungön. There is much to tell about the sometimes inhumanly harsh life on the island. Today it’s taken for granted that water comes when we turn on the tap and that lights shine when we flip the switch. We flush the toilet and when we feel cold we take a hot shower.

Page 1 #

The Jansson family on Lungön.

Here is a picture of the Jansson family. The place is Lungön just outside Härnösand and the year is 1919. It is one year before my mother Elsa is born and two years before the move to Högbonden. Between grandfather Knut and grandmother Augusta sit Arvid and Anna. To the left of grandfather sits the dog Bella. On Lungön one could live a relatively comfortable life. The proximity to Härnösand naturally contributed to this. On the island there was also a chapel, cemetery, a small shop, school, roads, permanent residents and great opportunities for vegetable gardening, which was one of grandmother Augusta’s very greatest interests. Högbonden lacked everything they had on Lungön but they had no choice but to move.

Page 2 #

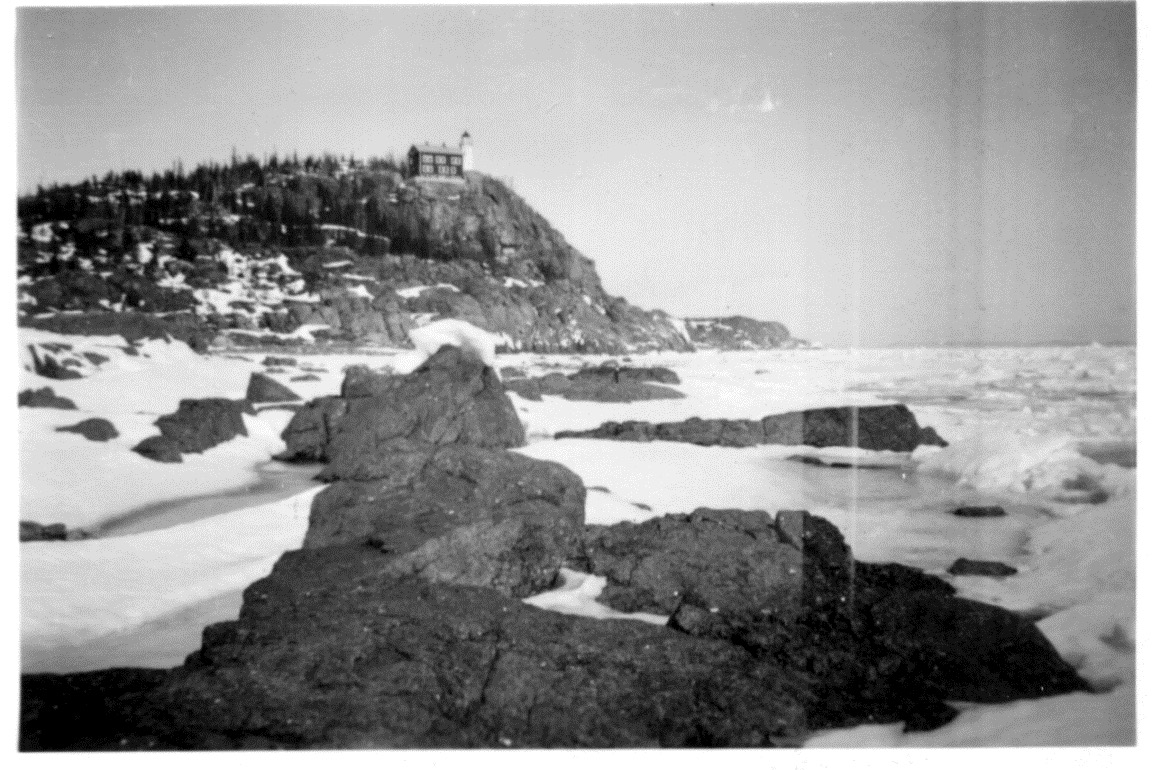

The move to Högbonden.

To this windswept rocky island my then one-year-old mother Elsa moved with her family in the autumn of 1921. Living on the island at the time were the lighthouse keeper Axel Söderblom and the lighthouse master Per Olof Sjöstedt with their families. The Jansson family initially had to live in the basement where the kerosene barrels were also stored. My uncle Arvid told me that in winter they moved the beds to the middle of the room since ice formed on the walls at night. The lighthouse assistant had the lowest rank and as one rose in the hierarchy the family could move up one floor. At the very top there was a school but it was closed the same year the Jansson family moved to the island. When it was time to start school, the Jansson children were boarded on the mainland. Anna in Rävsön, Arvid and Elsa in Näsänget. My mother Elsa told how she was teased for not speaking the Nordingrå dialect. The breaks were therefore what she dreaded most. In class, due to her nearsightedness, she had difficulty seeing what the teacher wrote on the board. She was placed at the very back of the classroom and at first didn’t dare tell anyone that she couldn’t see what the teacher wrote. The people of Bönhamn were probably unsure about what went on out on the island. They were regarded as heathens because they didn’t go to church. And then there was the fishing! The lighthouse staff mainly fished for cod and whitefish. The fishermen in Bönhamn fished for Baltic herring. My mother Elsa was often asked “Does your father fish for whitefish?” She often said that “he or she is so nosy you’d think they were from Bönhamn”!

Page 3 #

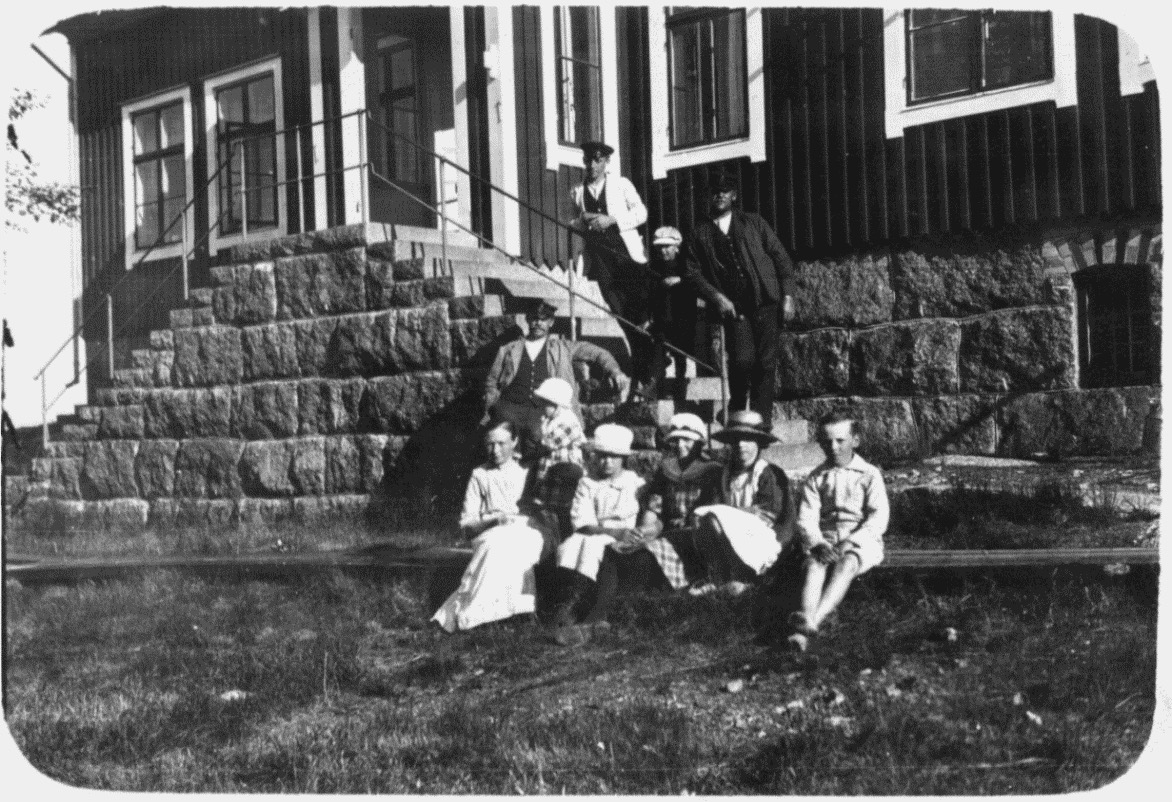

In this picture from 1924 (my guess), Per Olof Sjöstedt stands in a white lighthouse master’s coat at the top left. To his right stands my grandfather Knut Jansson, who was then serving as lighthouse assistant. Between Sjöstedt and grandfather stands uncle Arvid. Standing in front of the stone steps is the lighthouse keeper Axel Söderblom and in front of him my mother Elsa, born 1920. She would then be 4 years old in this picture, which I think is a reasonable guess. Seated furthest to the left is my grandmother Augusta. The girl with the big beautiful hat, seated as number two from the right, is mother and Arvid’s big sister Anna. The other children are presumably three of Söderblom’s five children.

The service distribution at a lighthouse station was lighthouse assistant, lighthouse keeper and lighthouse master. The lighthouse assistant had the lowest rank and the lighthouse master served as chief and work supervisor for the others.

The girl with the beautiful hat, Anna Jansson, will fall ill with tuberculosis and die four years later on the island at only 18 years of age. Per Olof Sjöstedt suffers a heart attack in 1935 up in the lighthouse tower. With great drama they manage to help him down the spiral staircase and with the cable car down to Klubbviken where, in rough weather, sitting in a chair, he was transported by a small utility boat to Bönhamn and then to the hospital in Härnösand. Normally one would never have gone out in such weather. According to my mother Elsa, who was then 15 years old, he survived the adventurous journey but died at the hospital in April 1935.

Page 4 #

The pier in Getviken.

It was nearly impossible to dock a boat at Högbonden as there is no natural harbor. A pier was therefore built in Getviken with a lifting device where the staff’s utility boats could be hoisted up. The first one built in 1928 was made of wood and disappeared quite soon in a storm. The pier in the picture was built of concrete in 1932 and has gradually been improved and expanded.

Page 5 #

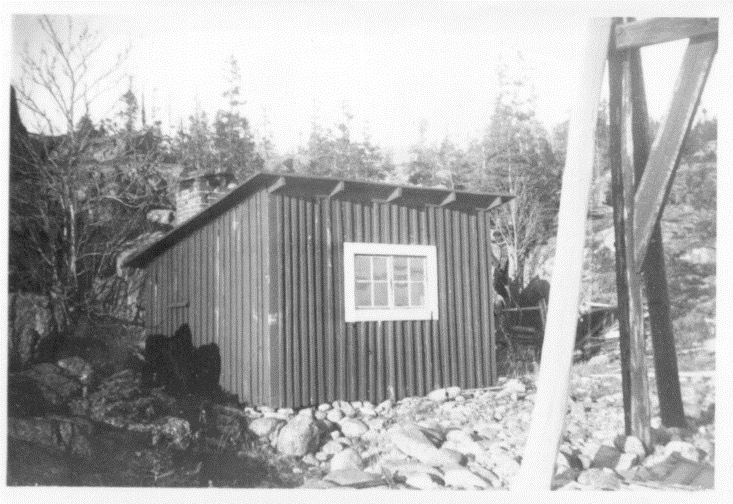

The smithy down in Klubbviken.

After several years of investigations and planning, construction of the lighthouse on Högbonden begins in August 1908. Down in Klubbviken, a crew barracks, storage shed, office and smithy were built. The smithy in the picture was thus one of the first buildings erected on the island. It was needed when the cable car was to be built, which in turn was a prerequisite for the lighthouse and residential building to be constructed. The building materials came to the island by boats and barges and had to be transported up to the high-located worksite 70 meters above the sea. To make room for the buildings, 36 cubic meters of rock had to be blasted away. The stone blocks were used for the foundation but first had to be split to suitable size and shape. The work was done by hand and was very time-consuming. The red bricks for the dwelling were manufactured at the Utnäs works north of Nyland on the banks of the Ångerman River. The bricks were transported on barges out to Högbonden and carted on so-called plank walks up to the cable car. The smithy is now gone but you can see remains of the hearth if you look carefully when walking down to Klubbviken. The rock behind the smithy is still called “Smithy Rock.” In the picture you can see the beginning of the cable car which continued to be a prerequisite for being able to live and work at the lighthouse station.

Page 6 #

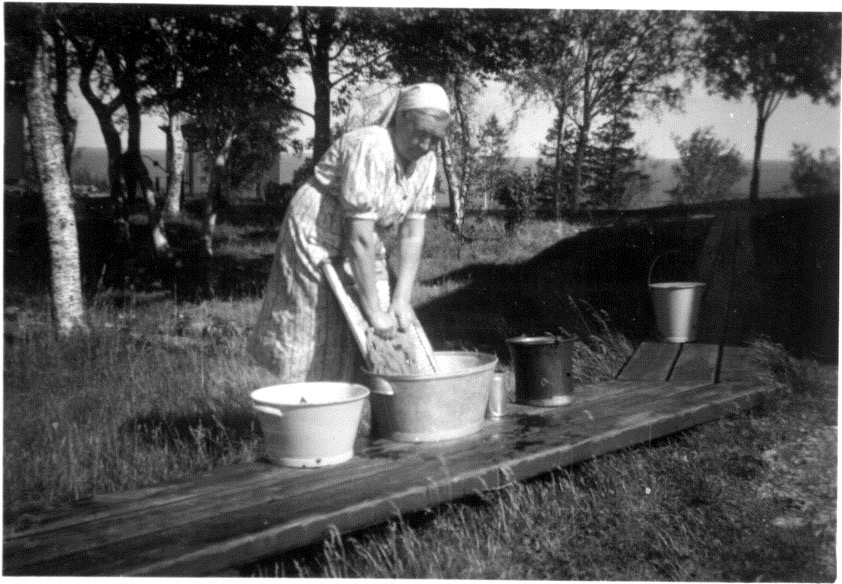

Augusta washing.

The lighthouse master’s wife Augusta has collected water for laundry. Washing was also done in summer down in Klubbviken. The lack of water was a constant problem. Drinking water had to be collected from pools that formed on the rocks after rain. In winter the only option was to melt snow. A deep-drilled well wasn’t obtained until 1944, but you had to pump for at least half an hour before any water came. In 1961 when “electricity came to the island” an electric pump was installed.

Before the lighthouse was lit on October 18, 1909, the lighthouse staff was tasked with draining the bog that extended right up to the house wall. At the end of the drainage a cemented well with an outlet was placed. There you could pump up a brown-colored bog water that left a dark sediment overnight. In the 1930s Sixten Söderblom found a statement about the water from a laboratory in Härnösand. It was described as unfit for human consumption, but usable for dishwater.

When I asked my mother Elsa what was the most difficult thing about life on the island, she unhesitatingly answered: the lack of water! She firmly maintained that they were sometimes forced to use the “bog water” for things other than dishes, but that no one got sick from it.

Page 7 #

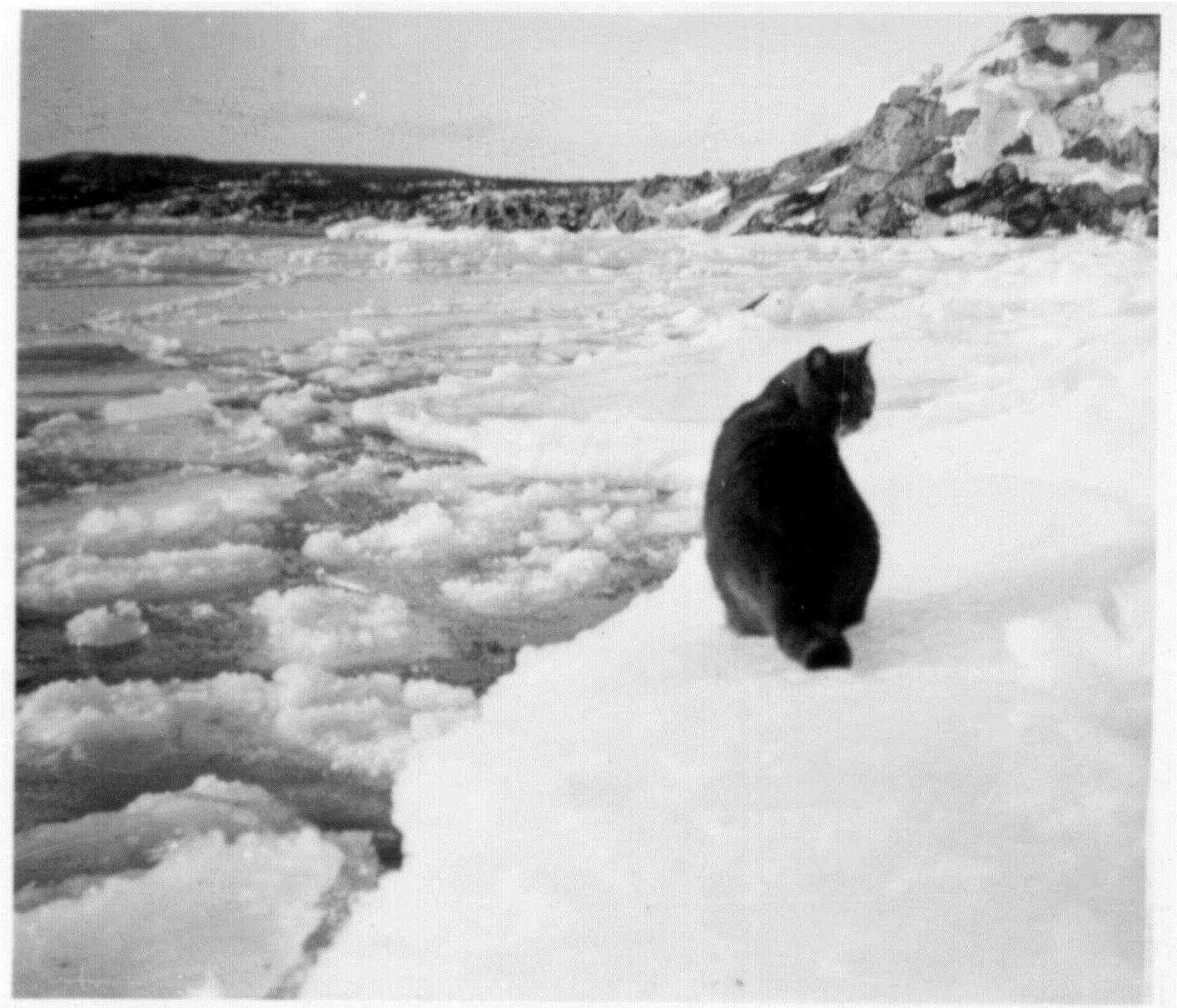

The tomcat “Sluggo” on the drift ice.

He is said to have courted lady cats in Barsta. Perhaps that’s where he’s heading. This time of year when the ice was breaking up, they would be isolated on the island for a while until they could use the boats again. If the wait became long, it happened that mail and food were dropped from an airplane.

Page 8 #

Grandfather Knut, here lighthouse assistant, and lighthouse master Sjöstedt in the small utility boat at Bönhamn. Why do they have a bicycle in the boat? Surely you can’t cycle on Högbonden? Of course not, but they used it to cycle to Näsänget to buy milk at a farm. Best to bring it out to the island so it won’t be stolen!

Page 9 #

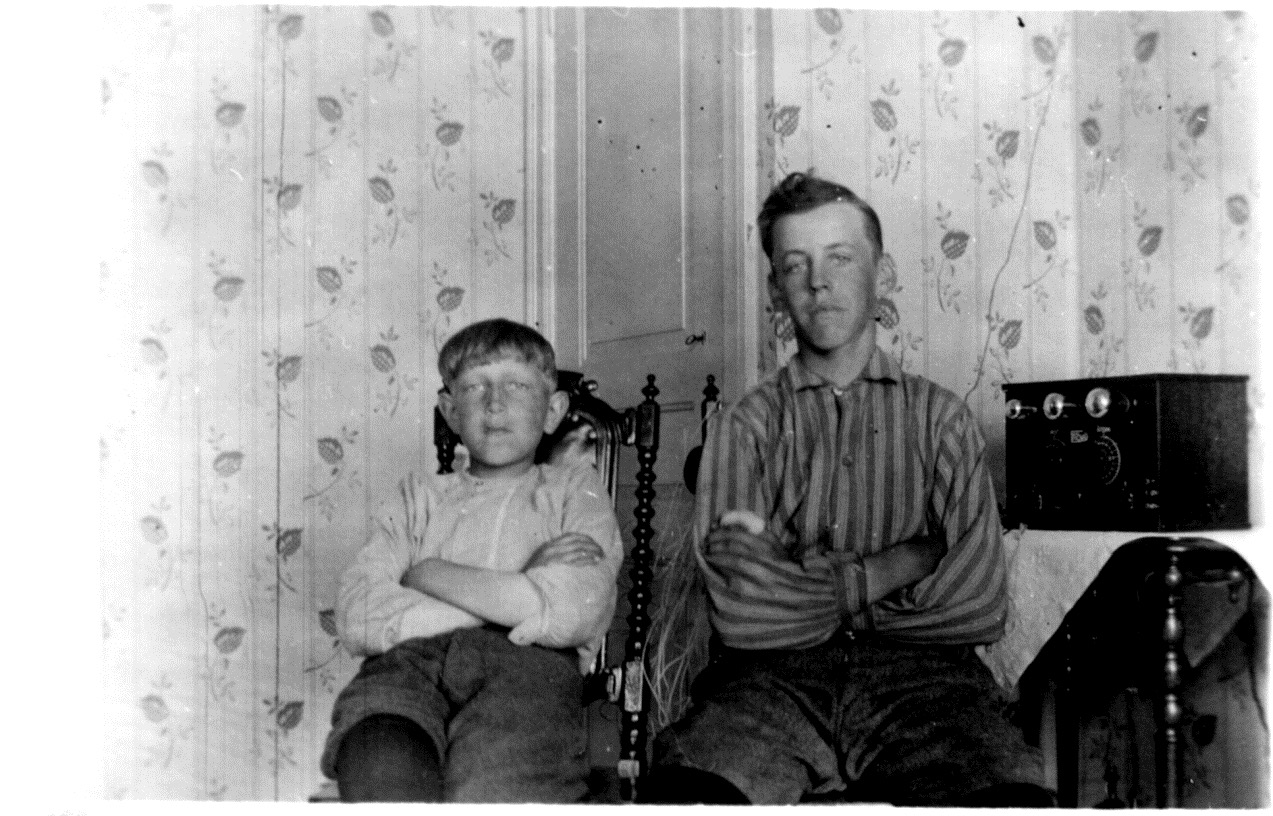

The Söderbloms were the first in the area to get a radio in the early 1930s. A Radiola. Fantastic! Arvid Jansson and Sixten Söderblom look solemn. Elsa’s comment on the back of the card.

Page 10 #

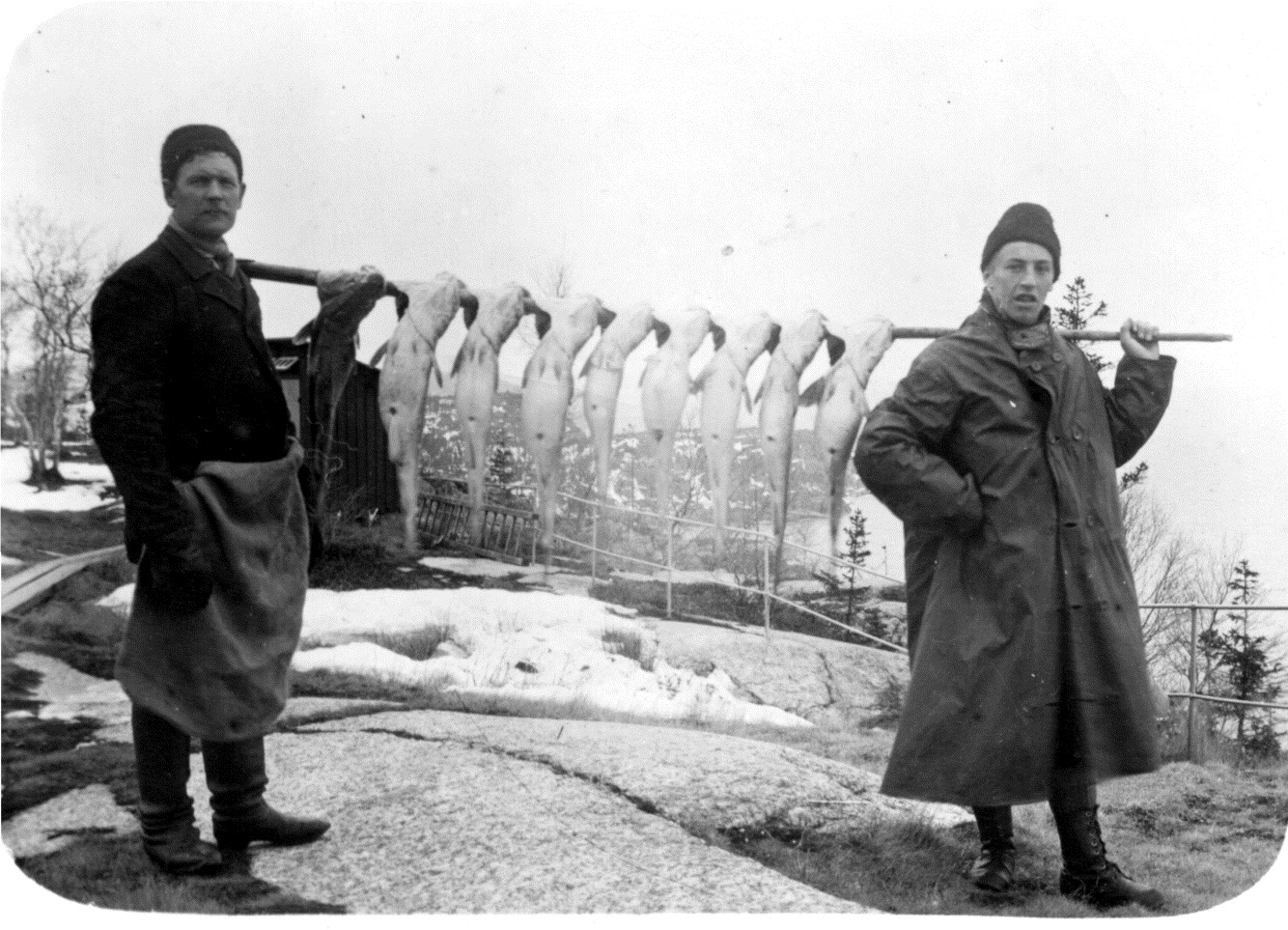

Knut Jansson on the left and Ossian Söderblom show off a successful cod catch. Ossian’s father Axel is lighthouse master and Knut is his lighthouse keeper. The picture is from the later part of the 1930s. Axel Söderblom became lighthouse master in the spring of 1935 and then succeeded Per Olof Sjöstedt.

Since the end of the 1500s there had been disputes about fishing along the Norrland coast. For those who want to know more about this, I recommend the chapter on Högbonden in Anders Hedin’s interesting book “Ljus längs kusten” (Light Along the Coast) from 1988.

The staff at the lighthouse stations traditionally had the right to fish for their own household needs. When the staff on Högbonden wanted to exercise this right, the local population opposed it, claiming they had exclusive rights to fishing in the waters around Högbonden. Lighthouse master Sjöstedt then sent an inquiry to his superior, the pilot captain in Gävle, who let the matter proceed to the Pilot Authority in Stockholm. After many turns and investigations, it was established that the lighthouse staff had the right to household fishing and the locals had to reluctantly accept that the lighthouse people were part of the fishing community. It happened that fishermen, while waiting to check their herring nets, would pull their boats up in Klubbviken and walk up to the lighthouse for a chat and a cup of coffee. Despite everything, there was quite a good atmosphere between fishermen and lighthouse folk.

Page 11 #

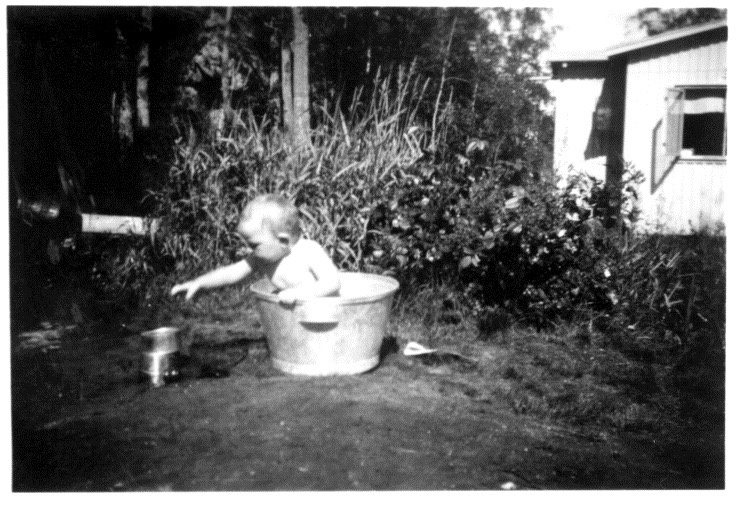

Ulla in the bath.

My big sister Ulla Jansson presumably has rainwater in the washtub. It could be the summer of 1944. In the background is what we called the “pilot’s cottage” where the so-called signalists lived during the war years. On the hill above the cottage there was an observation tower. When the signalists cooked, they would give Ulla samples through the window.

Page 12 #

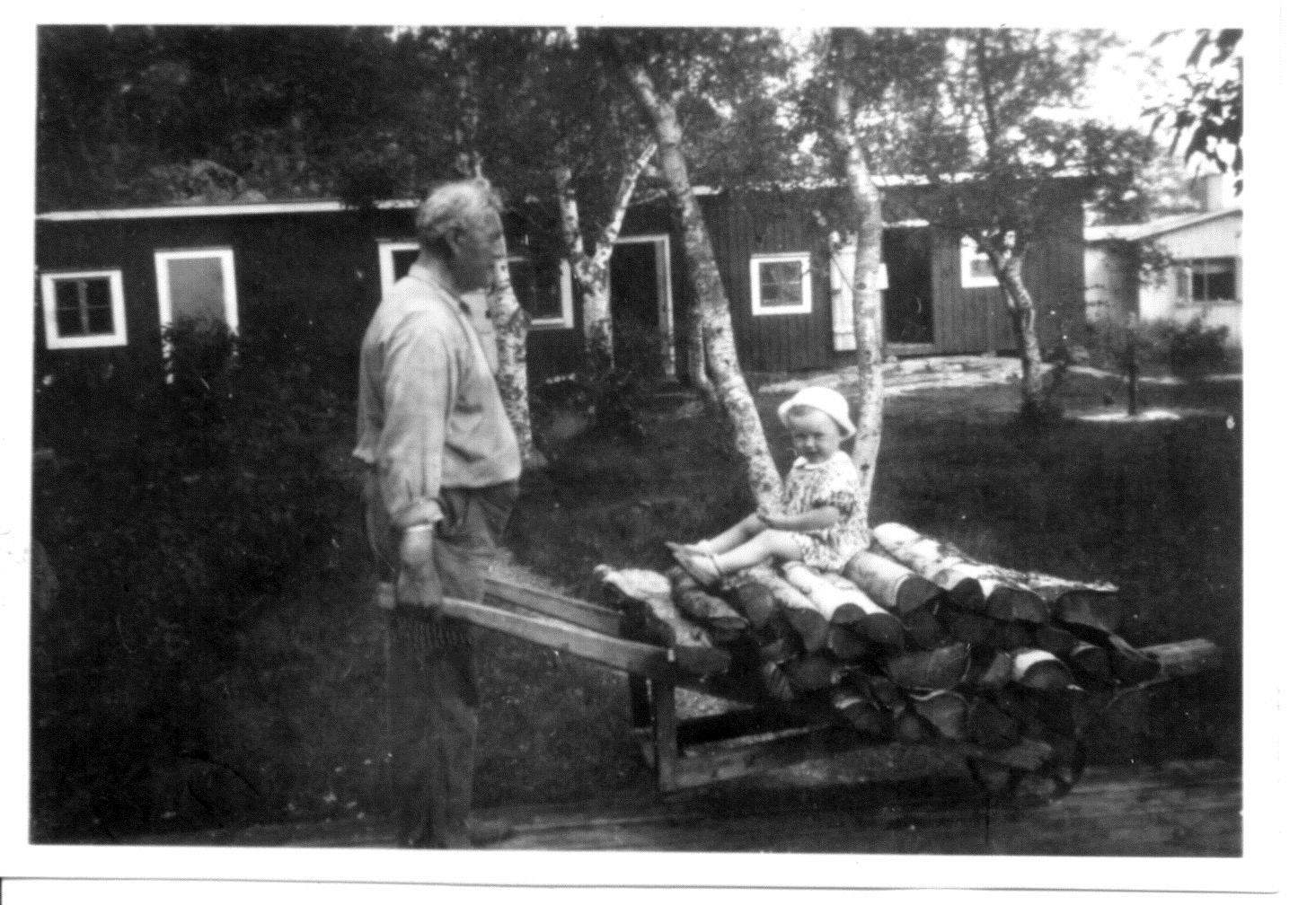

Grandfather and Ulla.

Knut Jansson with a load of birch firewood and the infant Ulla on the cart. The year is 1944. In the background you can see the outbuildings that now house the café, and on the far right you can glimpse the pilot’s cottage.

Page 13 #

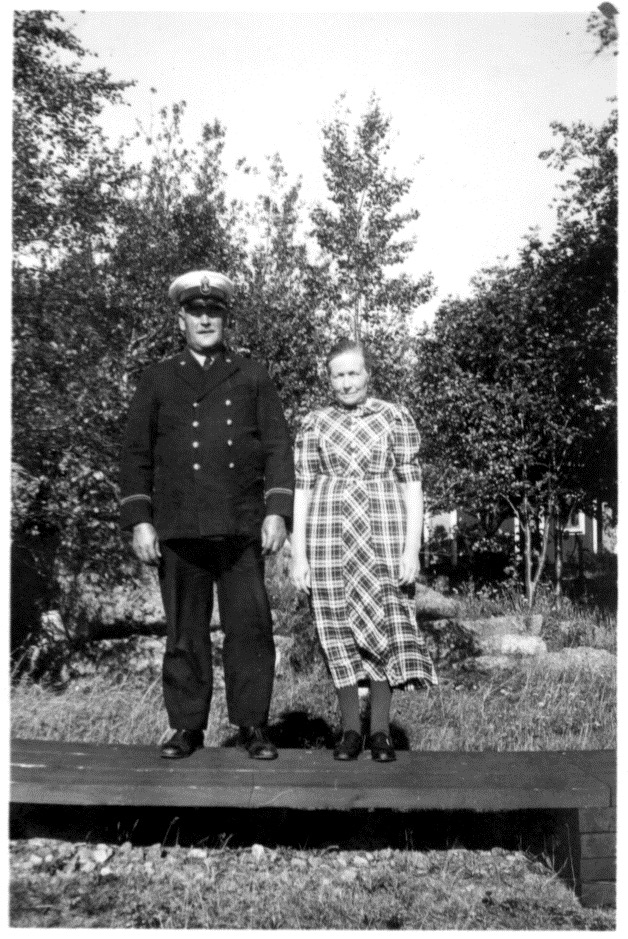

Lighthouse Master.

The Jansson couple on the courtyard. The year is 1943 and Knut is now lighthouse master. You can tell by the white cap cover that marked the lighthouse master title. The salary was not high and Augusta often said that instead of higher pay you got extra braids and gold buttons on the uniform. Nothing you could buy food with in Bönhamn!

Page 14 #

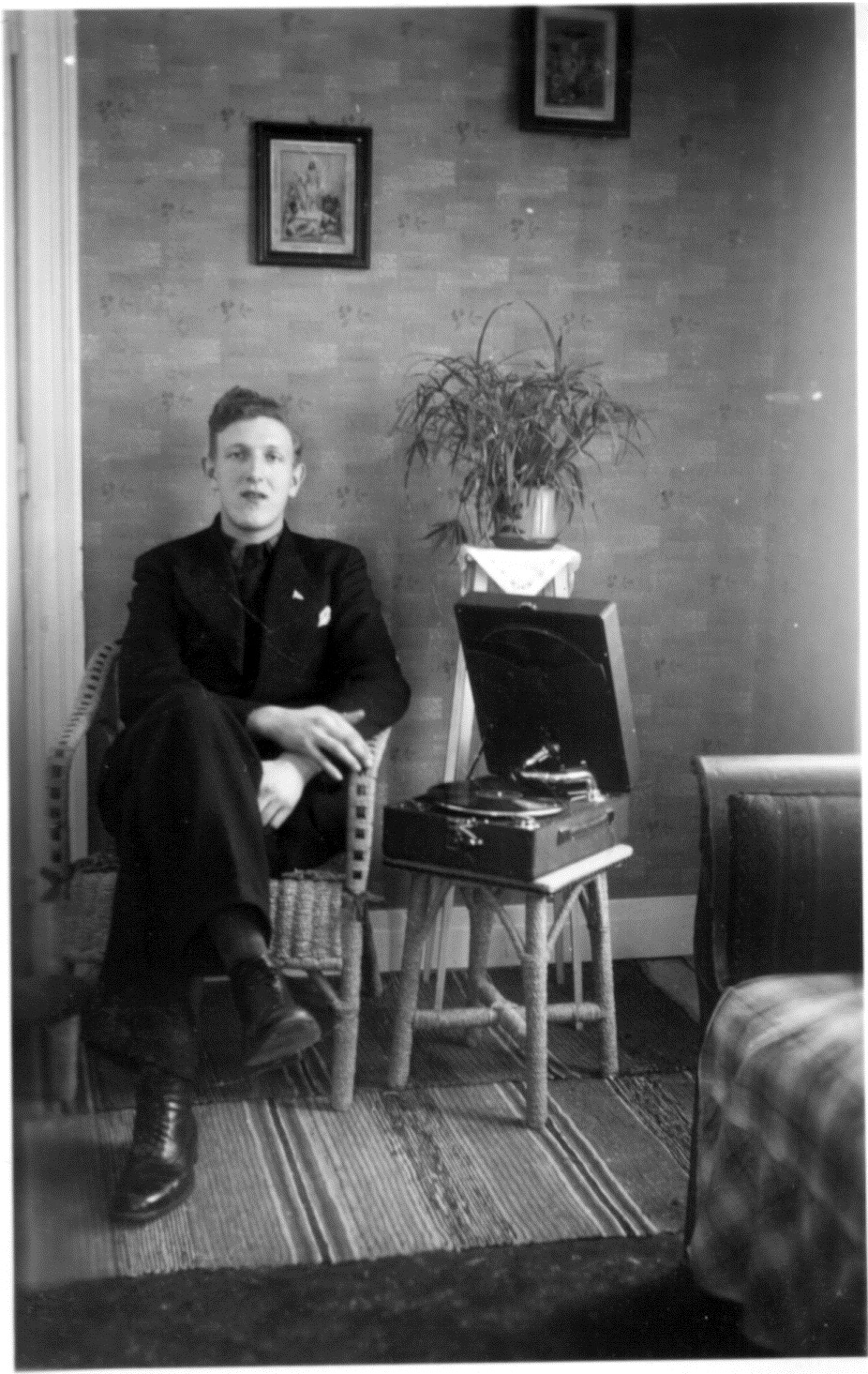

At the wind-up gramophone

My uncle Arvid with the wind-up gramophone on Högbonden. As a sailor he would sail around the world. This meant he came into contact with music of all kinds. Jazz music became a great interest that he kept for life.

Page 15 #

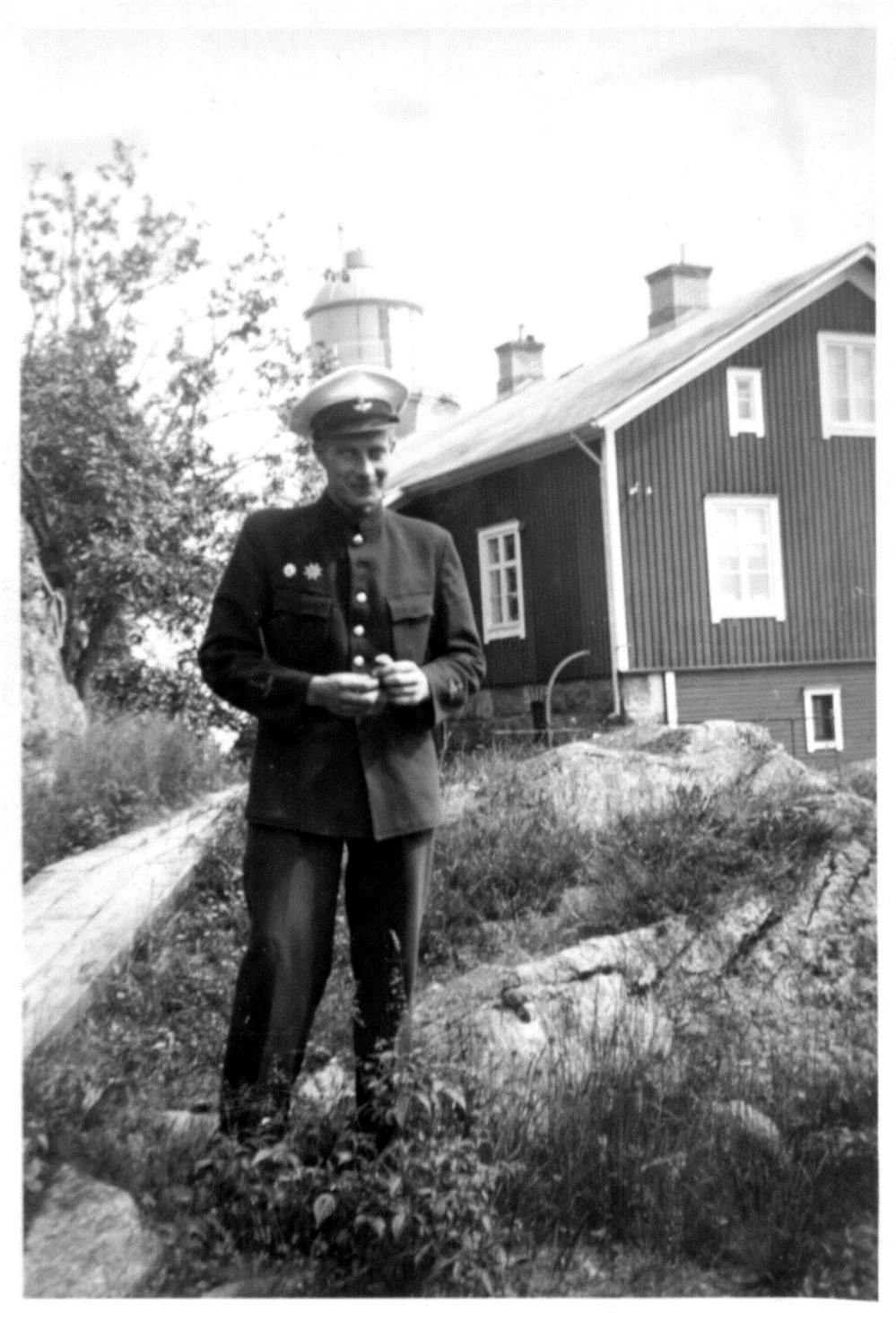

Cousin Robert visiting

Elsa and Arvid’s cousin Robert visiting. He got a free leave trip and took the opportunity to visit his relatives on Högbonden. Until 1943 the lighthouse was powered by kerosene. It was heavy work transporting the 180-liter barrels up to the lighthouse. The kerosene was stored in the basement. In the picture, at the left corner of the house, you can see the device where the pulley was attached when lowering the kerosene barrels to the storage in the basement. In the basement floor my grandfather’s family lived during the first period. Arvid told me that in winter they moved the beds to the middle of the room since ice formed on the walls.

Page 16 #

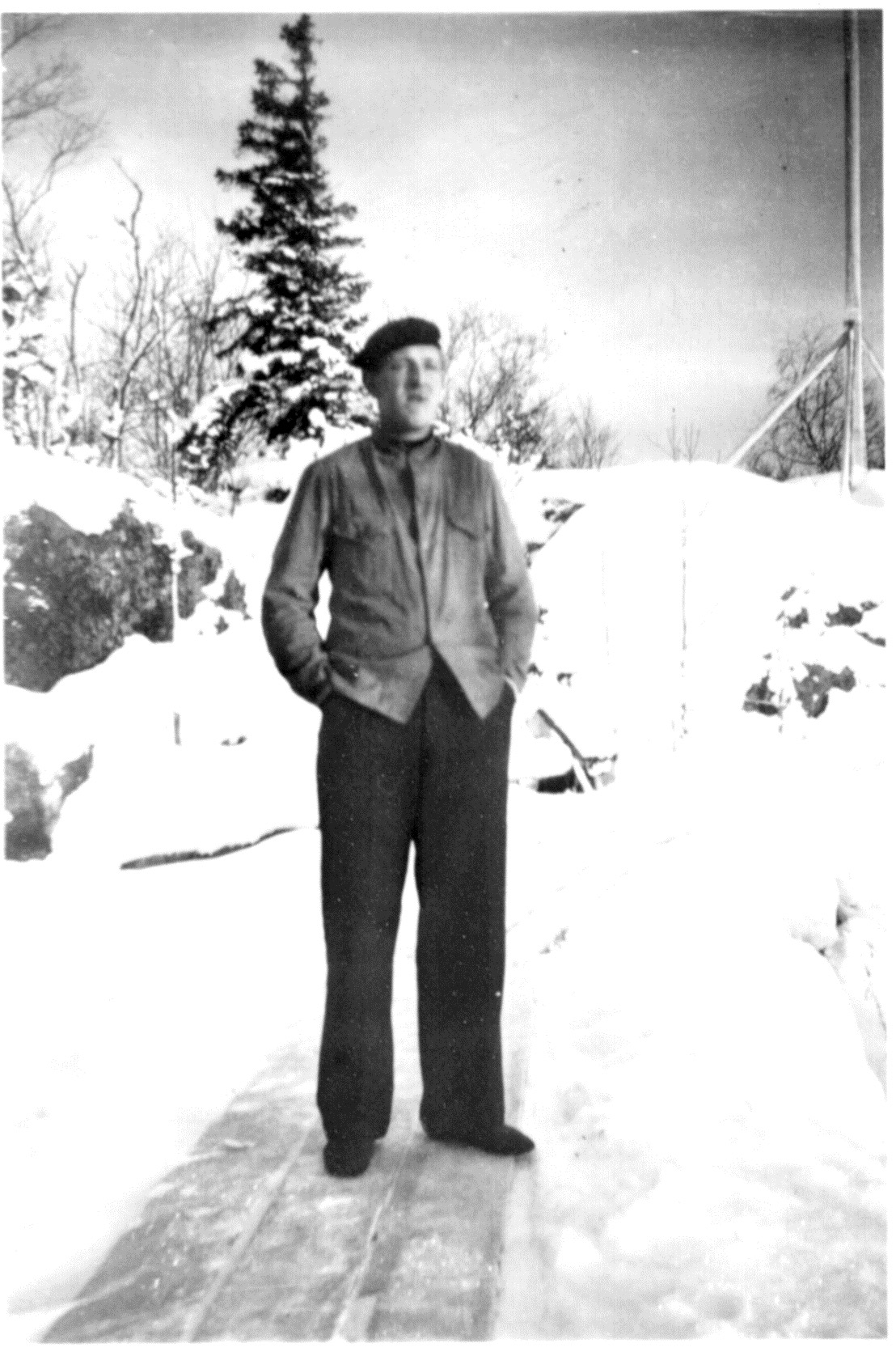

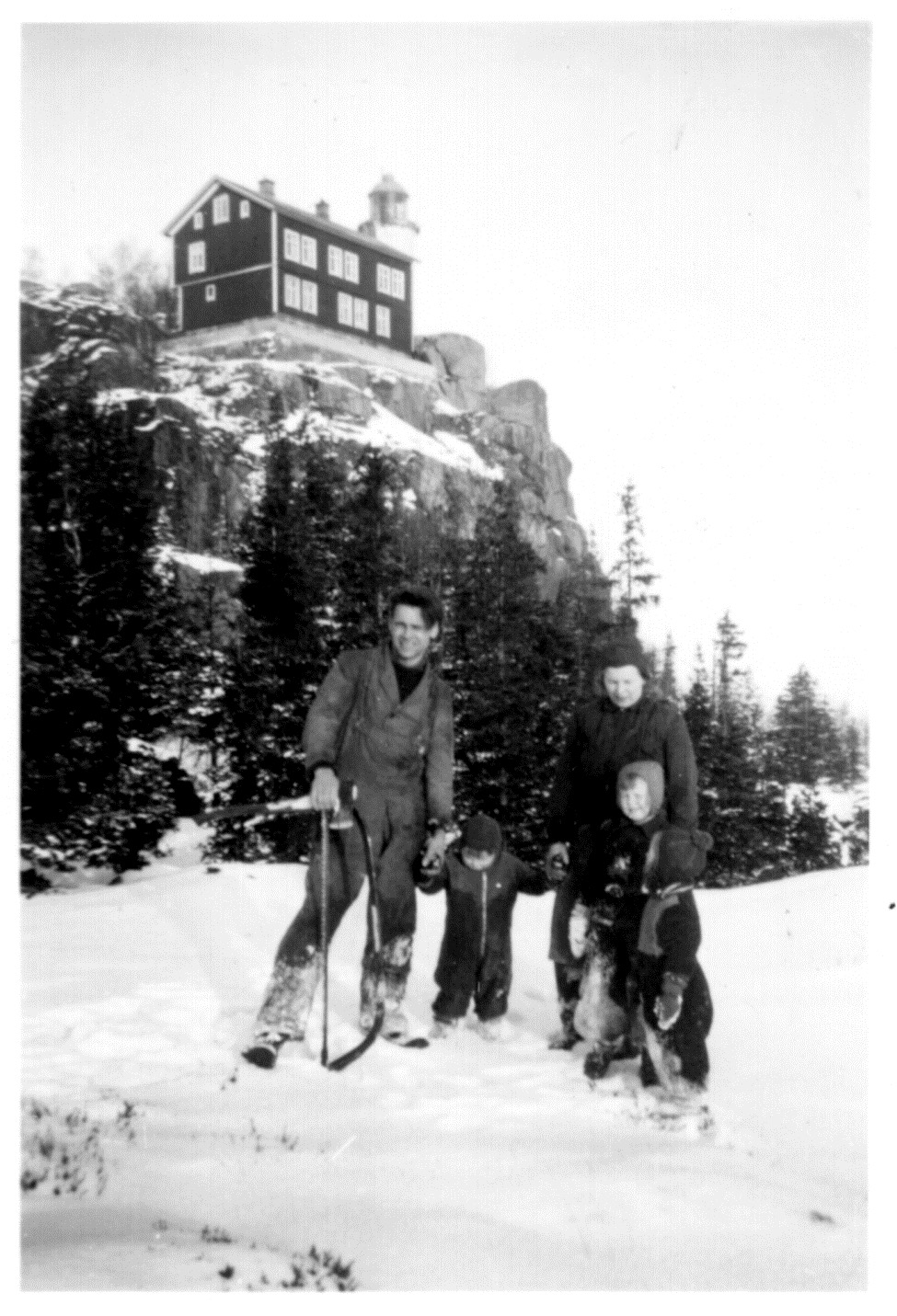

Uncle Arvid visiting winter 1945. Arvid was a sailor who sailed around the world. Very exciting for us to have such an uncle. Ulla says he thought she was spoiled and tried to raise her. She is said to have gotten angry and said “Go home to your America!”

Page 17 #

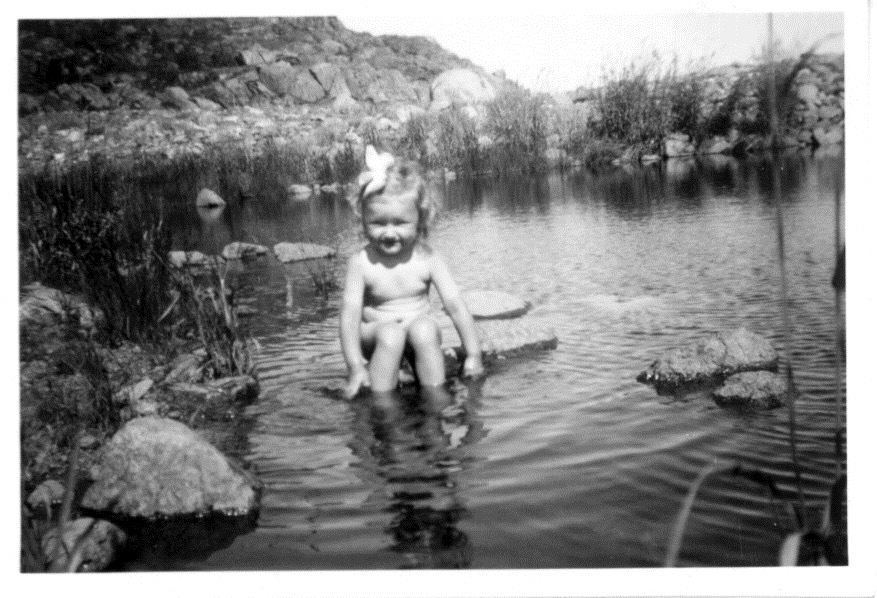

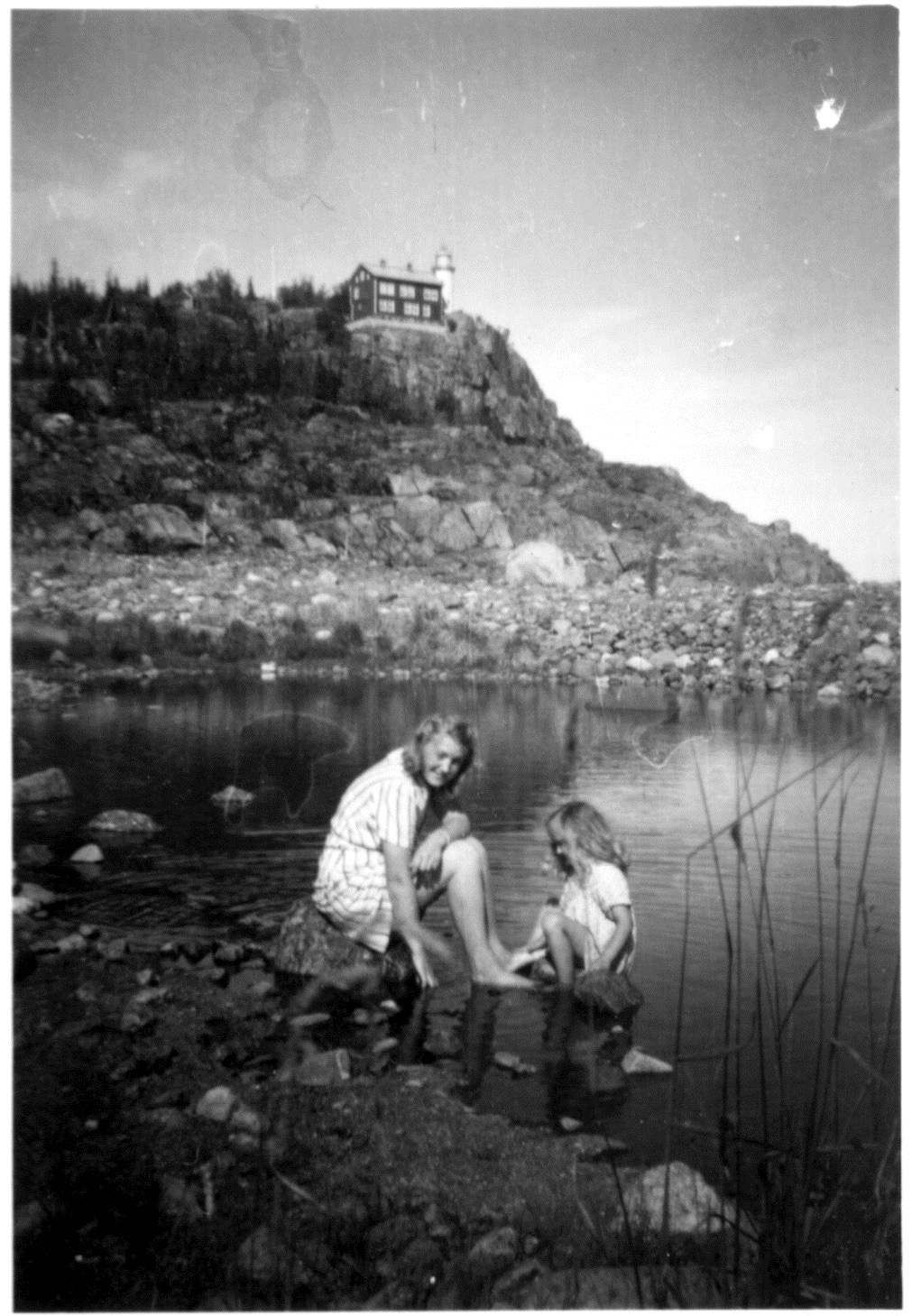

Ulla in Lillsjön (Little Lake).

Once there was a wide strait between Högbonden proper and its current southern tip Klubbudden. Due to post-glacial rebound, the strait eventually became a lake. Klubbviken was pretty much the only place where the children were allowed to play on their own. Not a fun playground among the rocks, but you had good oversight of your children from the lighthouse. Other terrain on the island was not so child-friendly.

Here my sister Ulla sits in “Lillsjön” down in Klubbviken. It was a popular bathing spot among the lighthouse staff’s children. The lake had a connection to the sea via a ditch that the staff was careful to keep open. Today the lake is dried up, partly due to land uplift and because no one maintains the ditch anymore.

Page 18 #

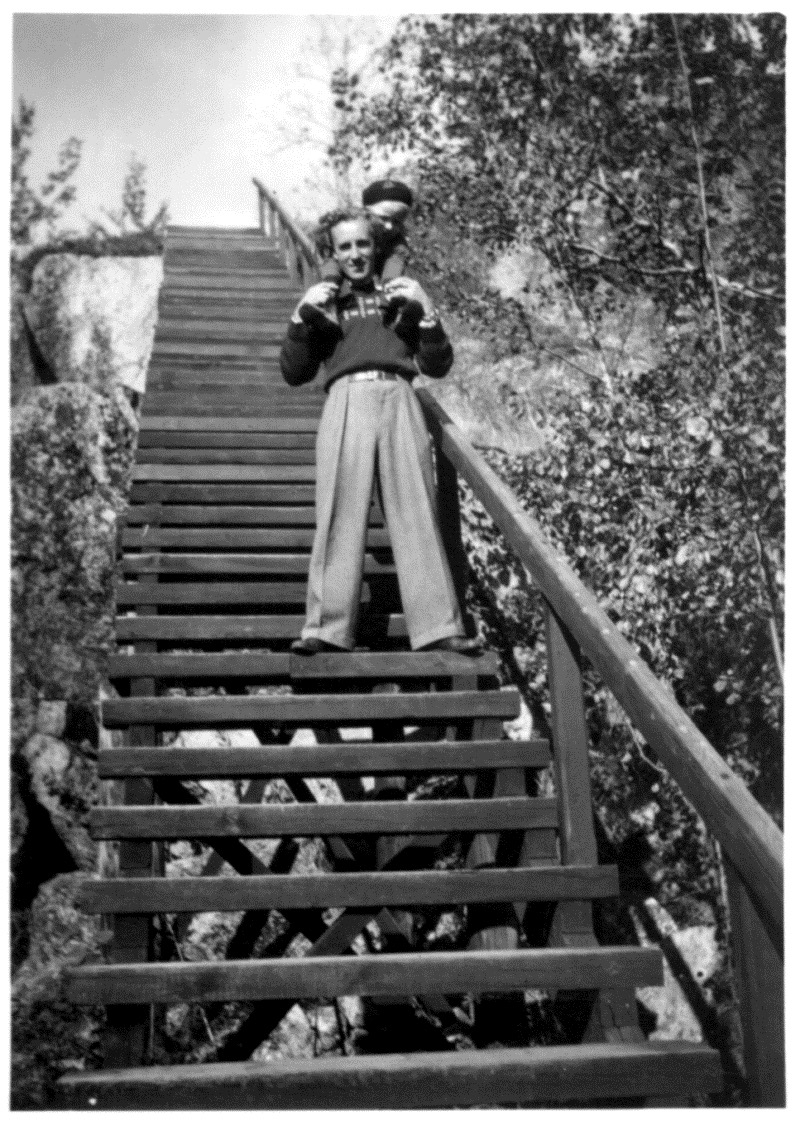

My father Henning Sundin and Ulla on the Grand Staircase with 52 steps.

The year is presumably 1946. My paternal grandfather Erik Johan Sundin was a tailor and sewed grandfather’s uniforms. That’s how Henning and Elsa met and eventually married. Henning adopted Ulla who was born out of wedlock. Ulla is thus my half-sister, something that was kept secret for a long time. In those days it was shameful! After all the “humorous” writings and “funny” songs about the lighthouse keeper’s daughter who got pregnant as soon as she left the island, my mother isolated herself in her old age and didn’t feel well. She took the writings to heart and was ashamed! Since not many lighthouse keeper’s daughters lived on the island, it wasn’t hard to figure out who it could be. That Högbonden became a tourist attraction didn’t make things better. She had difficulty understanding the sudden change from hard toil and hardship to luxury. She often said emphatically that “when we lived out there, we weren’t worth a rotten lingonberry. Now you can’t go shopping without Högbonden being on every bag”!

Page 19 #

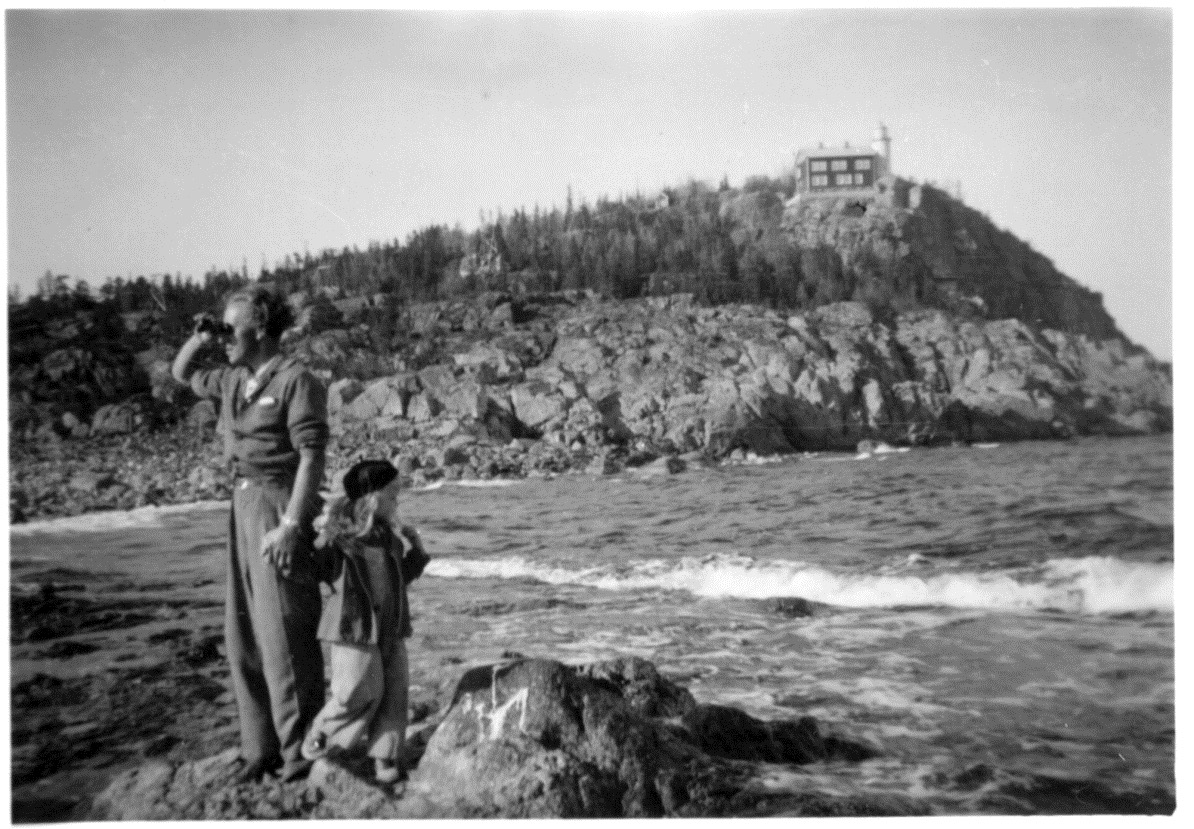

Henning and Ulla on Klubbudden.

Henning peers at something in the distance. The year is presumably 1946. My paternal grandfather Erik Johan Sundin was a tailor and sewed grandfather’s uniforms. That’s how Henning and Elsa met and eventually married. Henning adopted Ulla who was born out of wedlock. Ulla is thus my half-sister, something that was kept secret for a long time. In those days it was shameful! After all the “humorous” writings and “funny” songs about the lighthouse keeper’s daughter who got pregnant as soon as she left the island, my mother isolated herself in her old age and didn’t feel well. She took the writings to heart and was ashamed. Since not many lighthouse keeper’s daughters lived on the island, it wasn’t hard to figure out who it could be. That Högbonden became a tourist attraction didn’t make things better. She had difficulty handling the sudden change from hard toil and hardship to luxury. She often said emphatically that “when we lived out there we weren’t worth a rotten lingonberry! Now you can’t go shopping without Högbonden being on every bag”!

Page 20 #

Christmas 1946.

Lighthouse keeper Ivar Kyhlberg with children Inger and Lasse and Elsa Jansson with daughter Ulla. It’s Christmas 1946 and they’re about to saw a Christmas tree.

Page 21 #

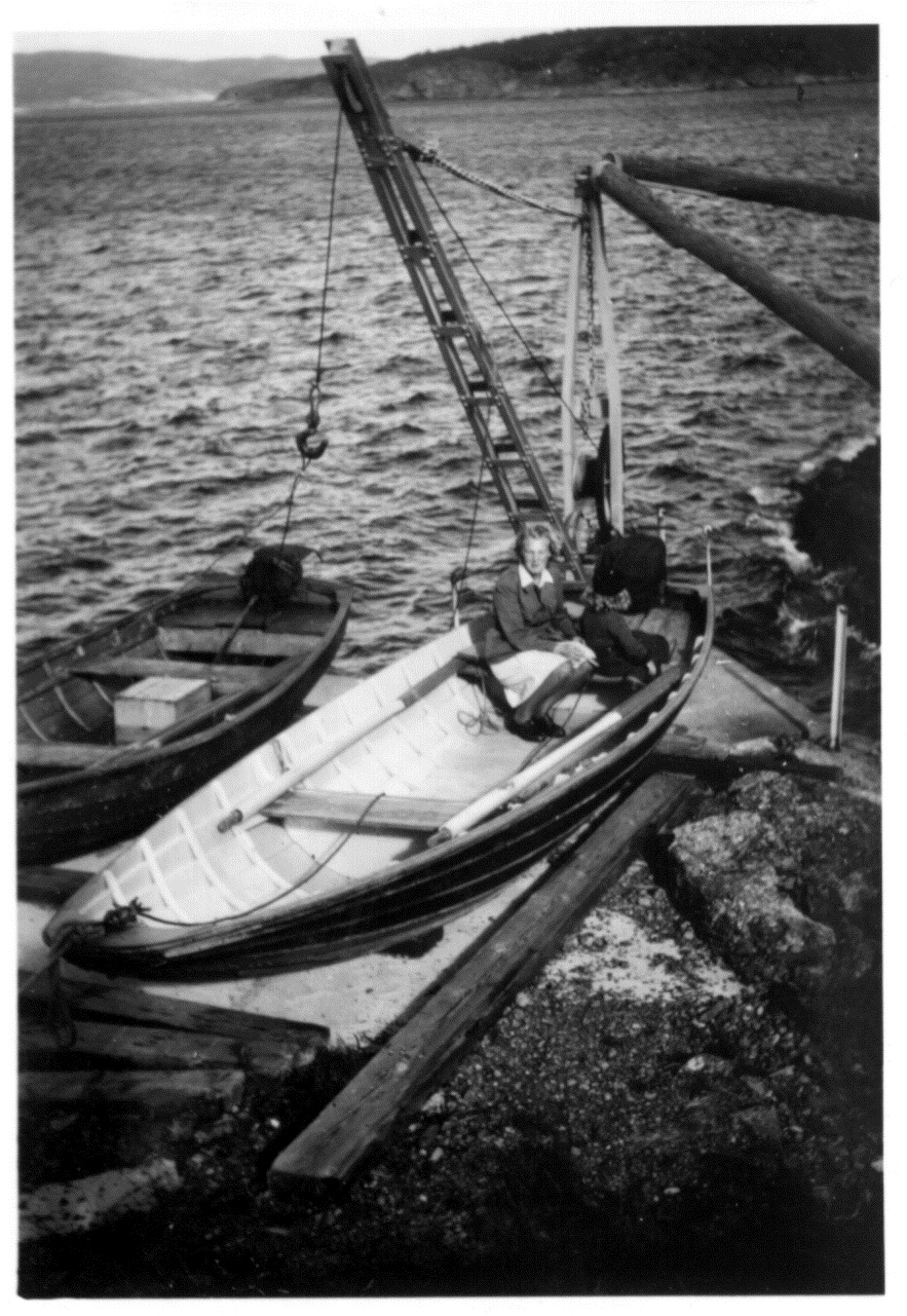

Elsa and Ulla in the hoisted large utility boat called “Sampo.” In the background you can see Höglosmen.

Page 22 #

Summer 1947.

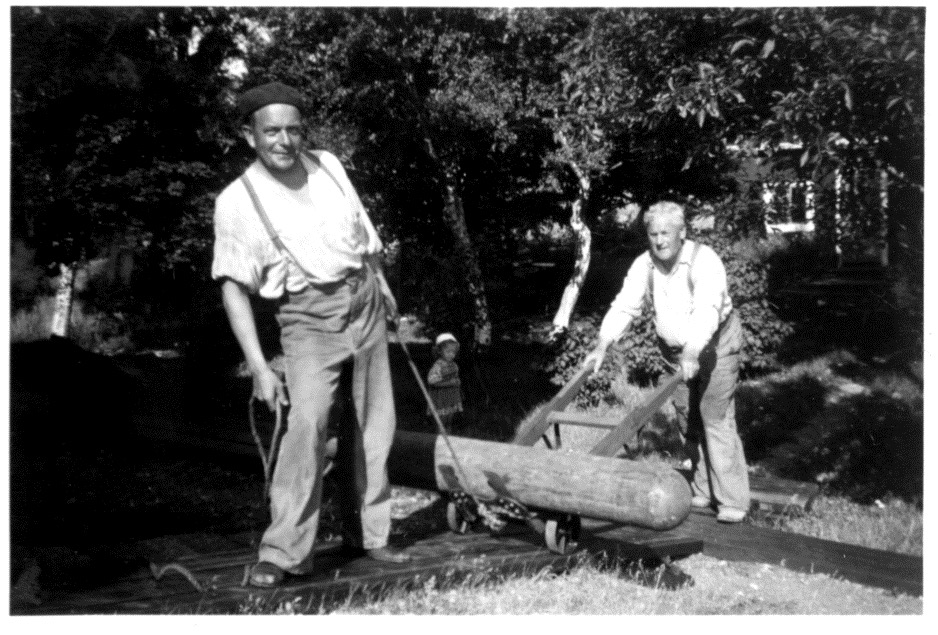

The same year grandfather Knut became lighthouse master (1943), the old kerosene incandescent light was replaced with a gas-powered system, so-called Dalén light, which meant that staffing needs decreased. This picture is from summer 1947. It’s the last summer on Högbonden. Grandfather and Lundgren, a temporarily employed helper during the final time on the island, are transporting a gas cylinder. Before the Dalén light, the lighthouse functioned like a giant kerosene lamp and required constant attention to adjust the flame. It was important not to fall asleep on one’s watch. My mother Elsa told me that grandfather knitted socks to stay awake but that grandmother helped him with the “heel turn.”

Page 23 #

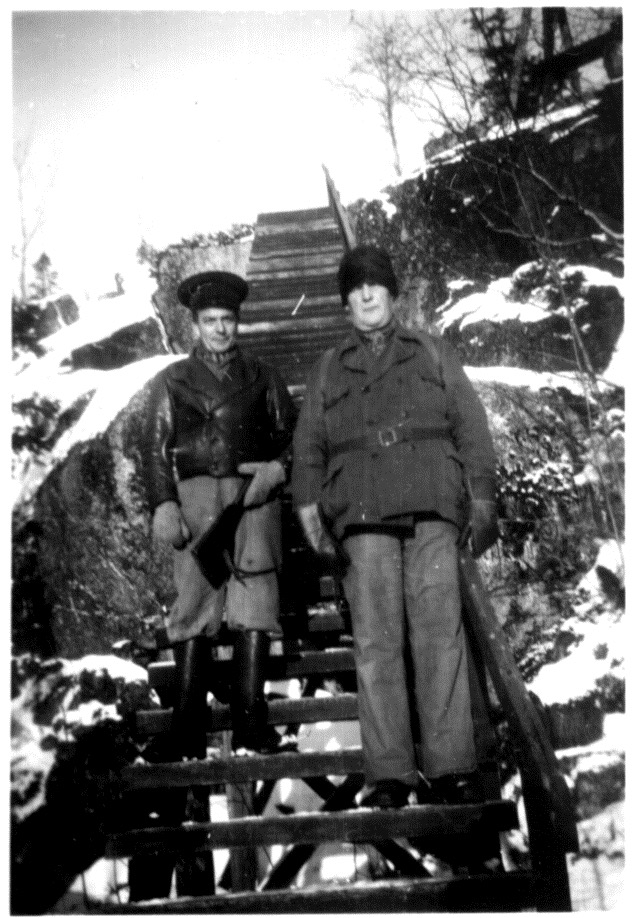

Spring 1947

Lighthouse keeper Ivar Kyhlberg has taken a position at Östergarn lighthouse and was replaced by a man who according to my mother was named Lundgren. Here he poses together with grandfather on the grand staircase. It looks cold and Lundgren has a rifle under his arm. What was hunted is uncertain. Perhaps seal or bird. Maybe they simply arranged a fun picture.

Page 24 #

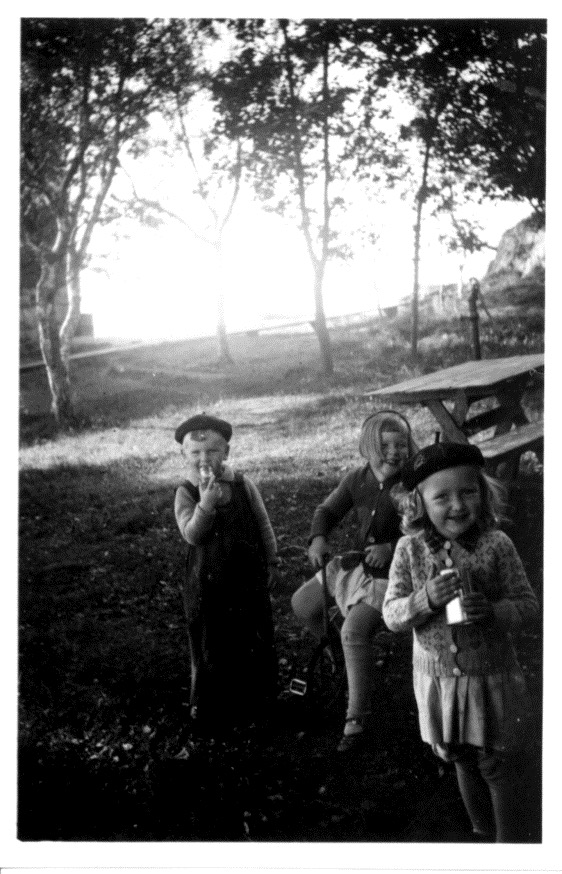

Children in the courtyard.

In front stands my sister Ulla with Inger and Lars, whose father Ivar Kyhlberg served as lighthouse keeper during grandfather’s final years at the lighthouse. Until then Ulla had been the only child on Högbonden, and it was of course wonderful to have the company of other children. Here they’re celebrating with a Pommac!

Page 25 #

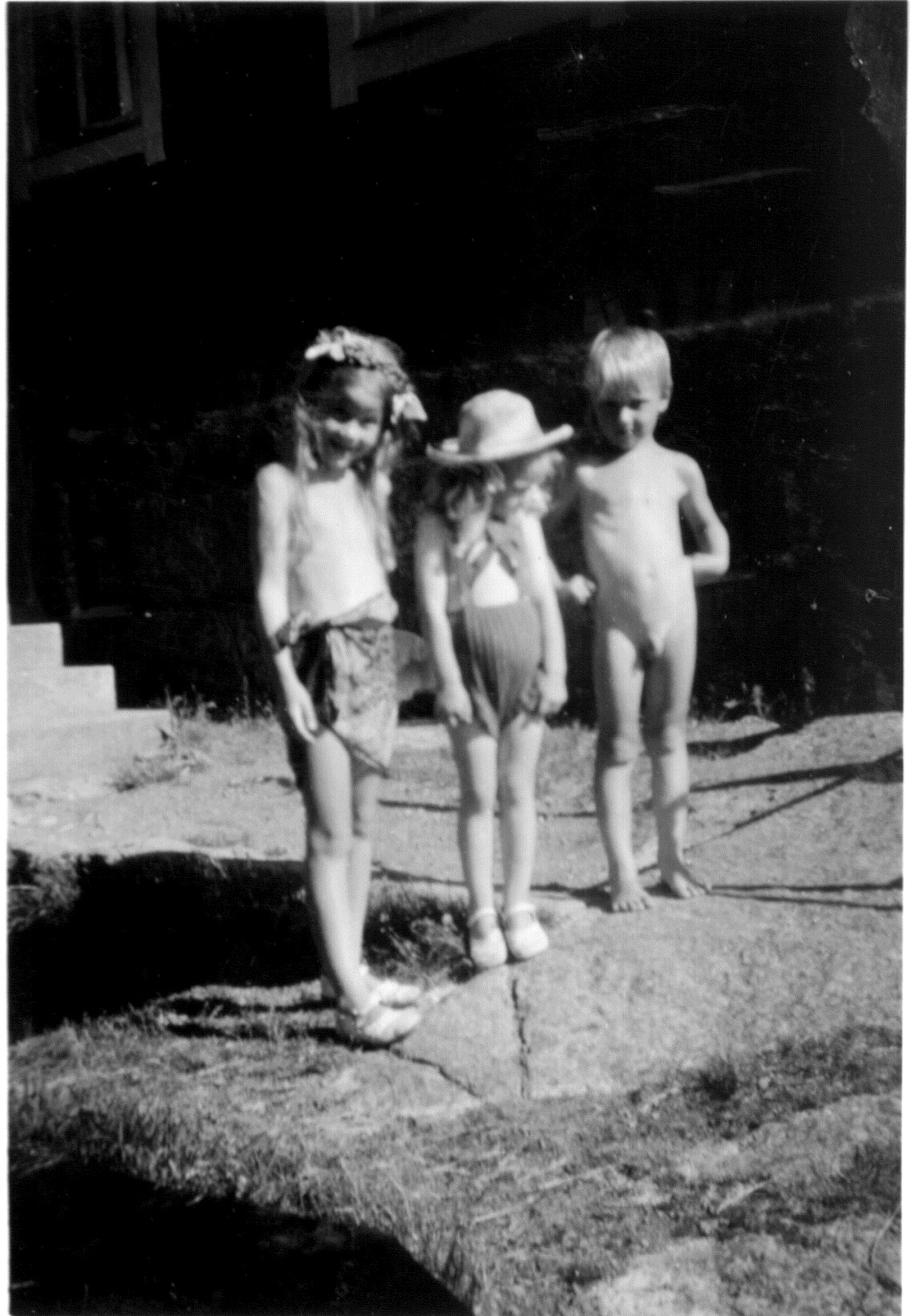

Children visiting. Ulla looks wonderingly at a naked boy. It wasn’t often that other children came to visit and especially not naked boys, one might think.

Page 26 #

Lillsjön.

A shame that Lillsjön no longer exists. In summer 1947 it was a great joy for Ulla Jansson and mother Elsa.

Page 27 #

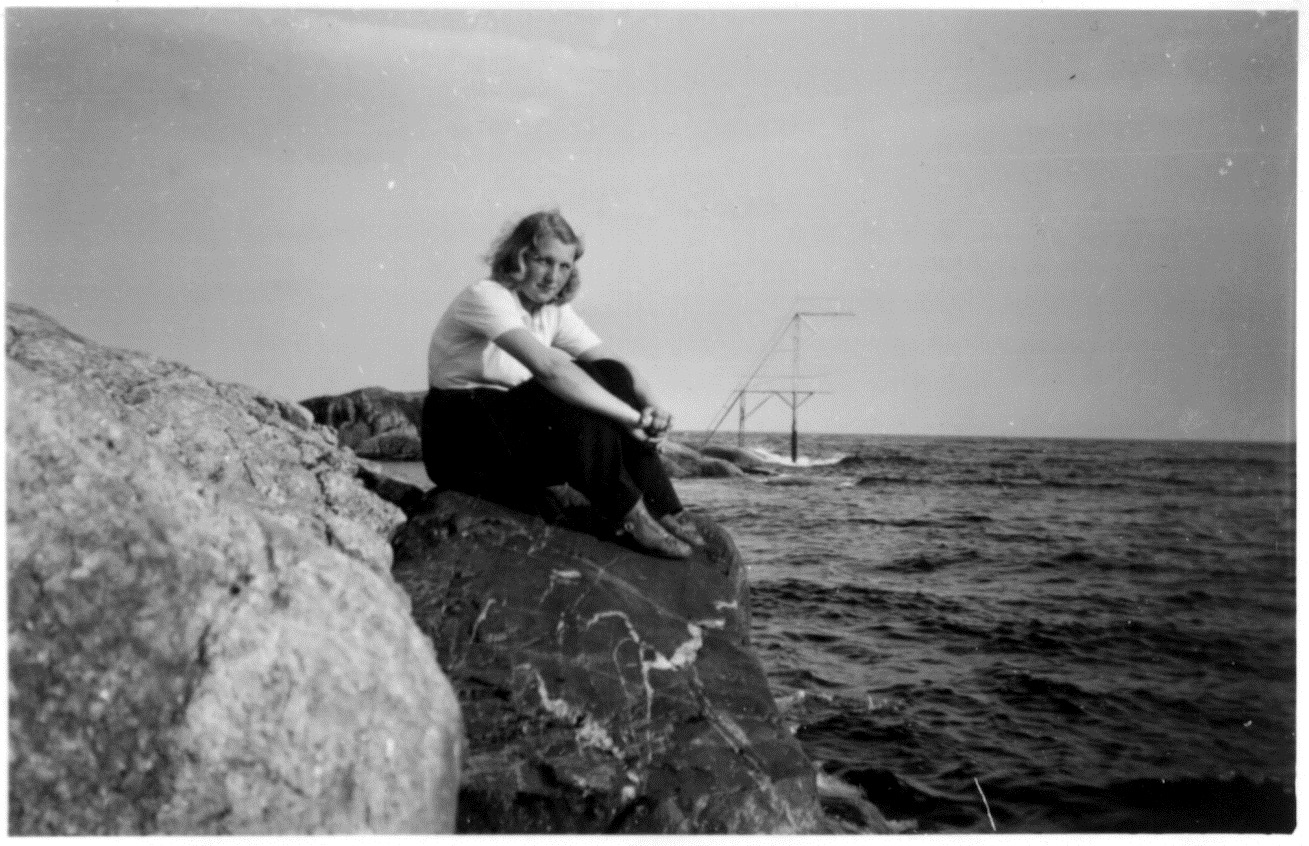

My mother Elsa Jansson sits on Smithy Rock and gazes out over the sea. The time is sometime in the early 1940s. Out at the far end of Klubbudden you can see a structure that I was long unsure about what function it could have had. In the Lighthouse Society’s book “Fyr- och sjömärkeslistan” (Lighthouse and Sea Marks List), I can find the answer to my wondering. It’s a so-called sea mark that indicates the fairway boats should choose to avoid running aground. Like much else, it has long since disappeared.

Page 28 #

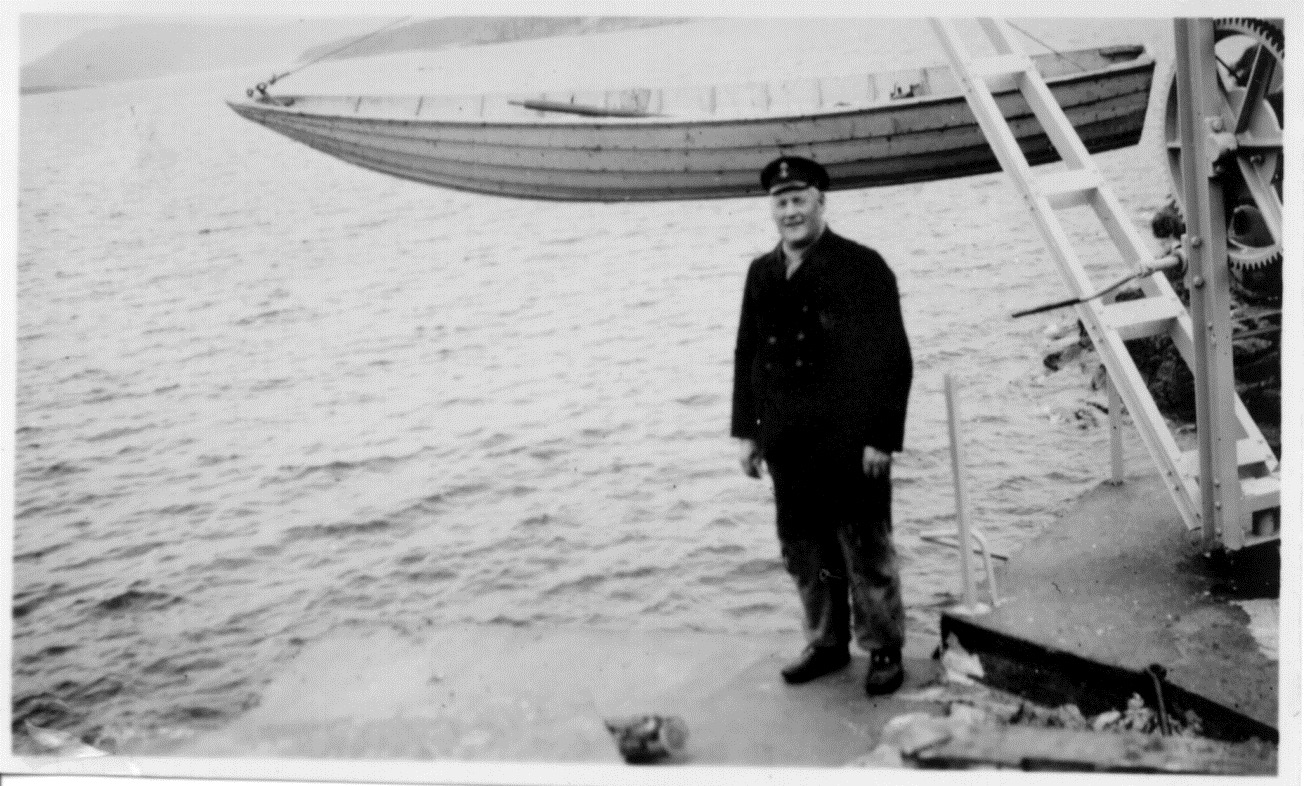

Grandfather at the boat lift.

In this picture Knut Jansson has hoisted up the boat after a trip to Bönhamn. Since there was no natural harbor on the island, the utility boats had to be hoisted up after use to avoid being crushed against the cliffs. When I last visited the island, the lifting device was dismantled! Will the next step be to dismantle the original cable car that was vital for the staff? The smithy has long been gone. It feels increasingly justified to document the arduous life on the island in words and pictures.

Page 29 #

Visiting the Näsholm family.

When Elsa was to start school, she was boarded with the Näslund family in Näsänget. In this picture grandmother Augusta and Ulla are visiting Mrs. Näsholm. Nice for grandmother to get an outing and get away from the island.

Page 30 #

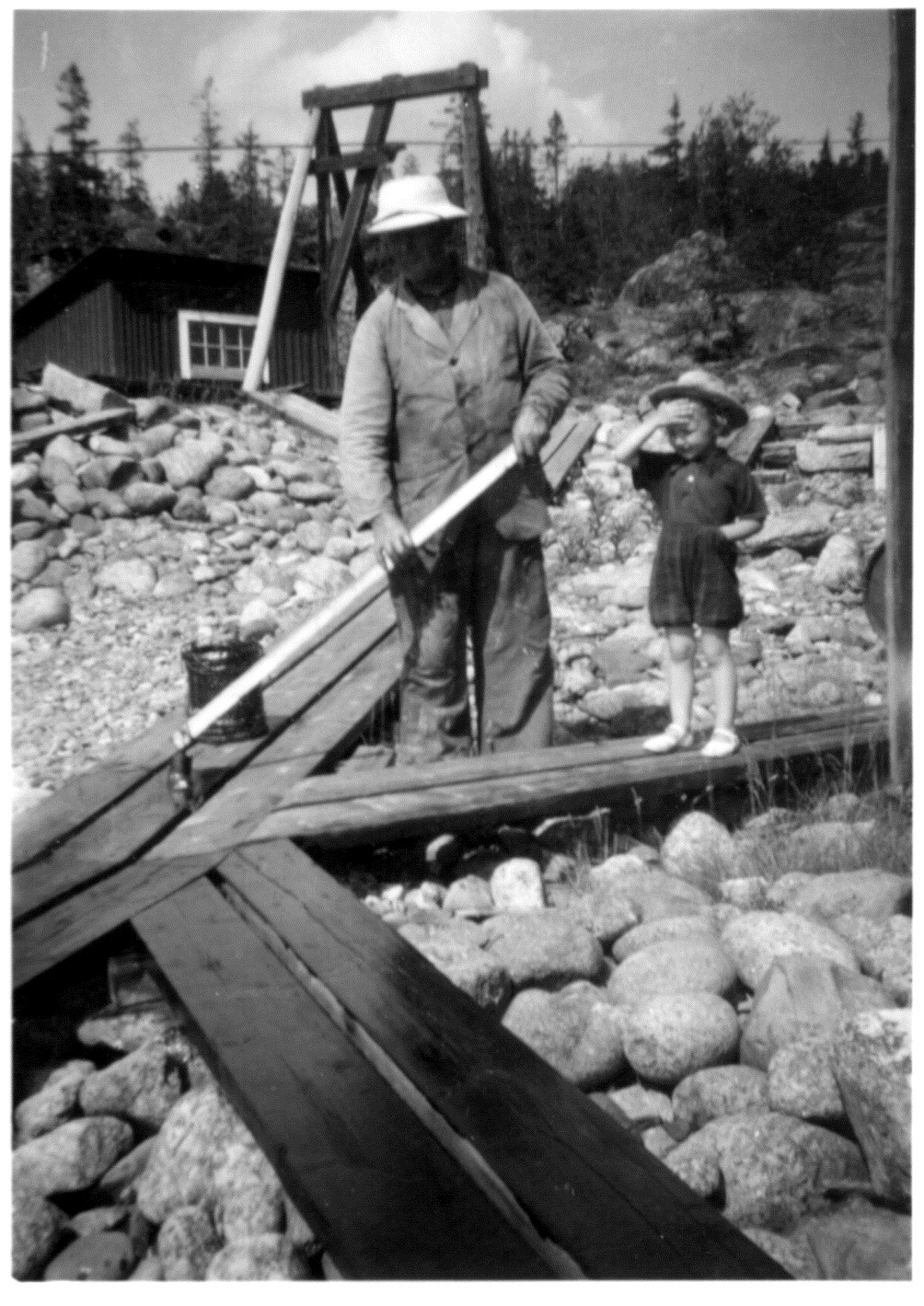

Summer 1947. Lighthouse master Knut Jansson is tarring the plank walks down in Klubbviken. He retires on September 30 that year but dutiful as he is, he wants to leave things nice. To help him he has his granddaughter Ulla who puts her hand to her forehead. It’s hot and grandfather is wearing the pith helmet that Arvid brought from one of his voyages. In the background you can see the smithy and the first part of the cable car.

Page 31 #

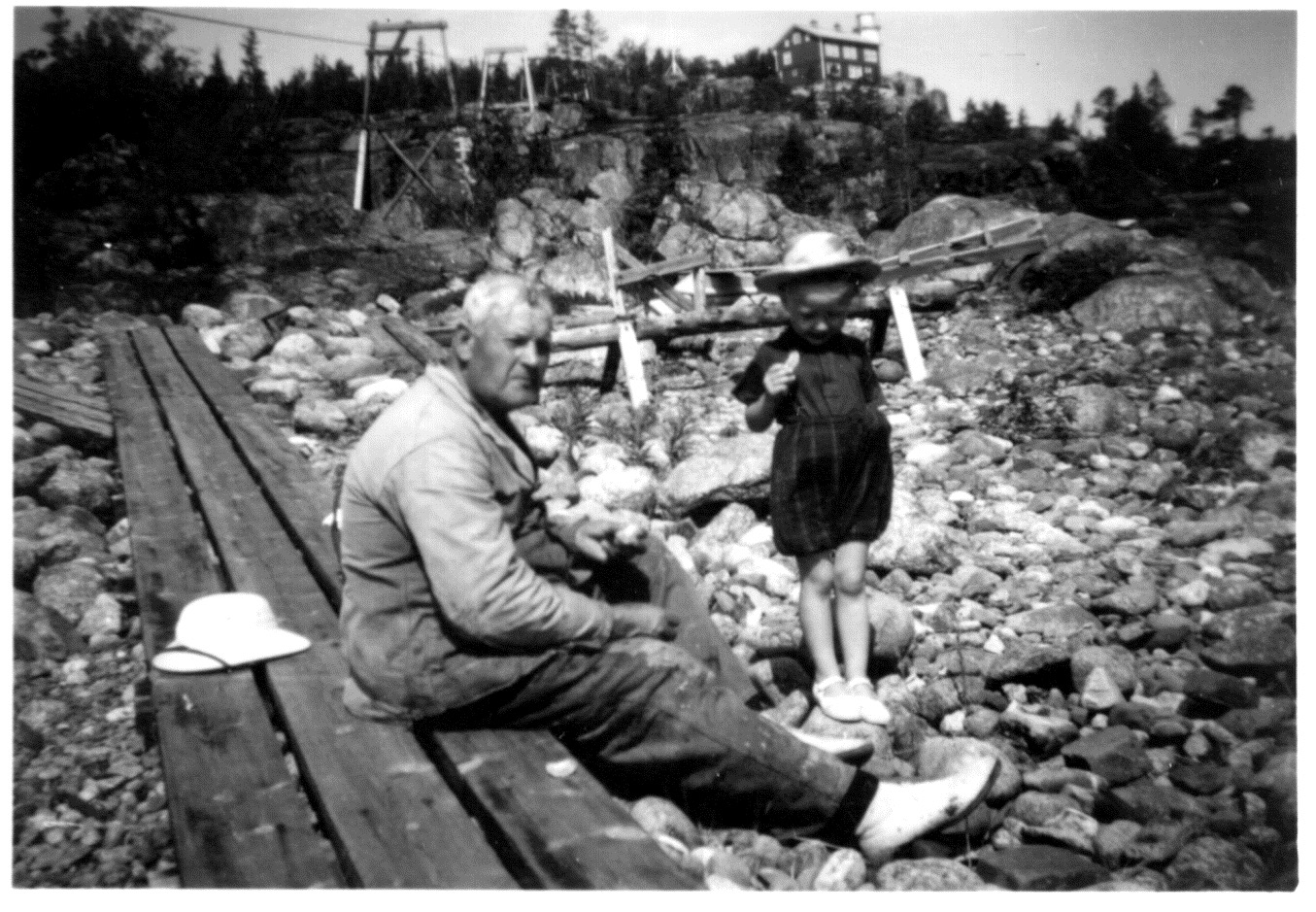

Break from work.

Here they take a break from tarring the plank walks. Knut looks tired and worn! It’s the last summer on the island and it’s probably with mixed feelings that he thinks about retiring in the autumn.

Page 32 #

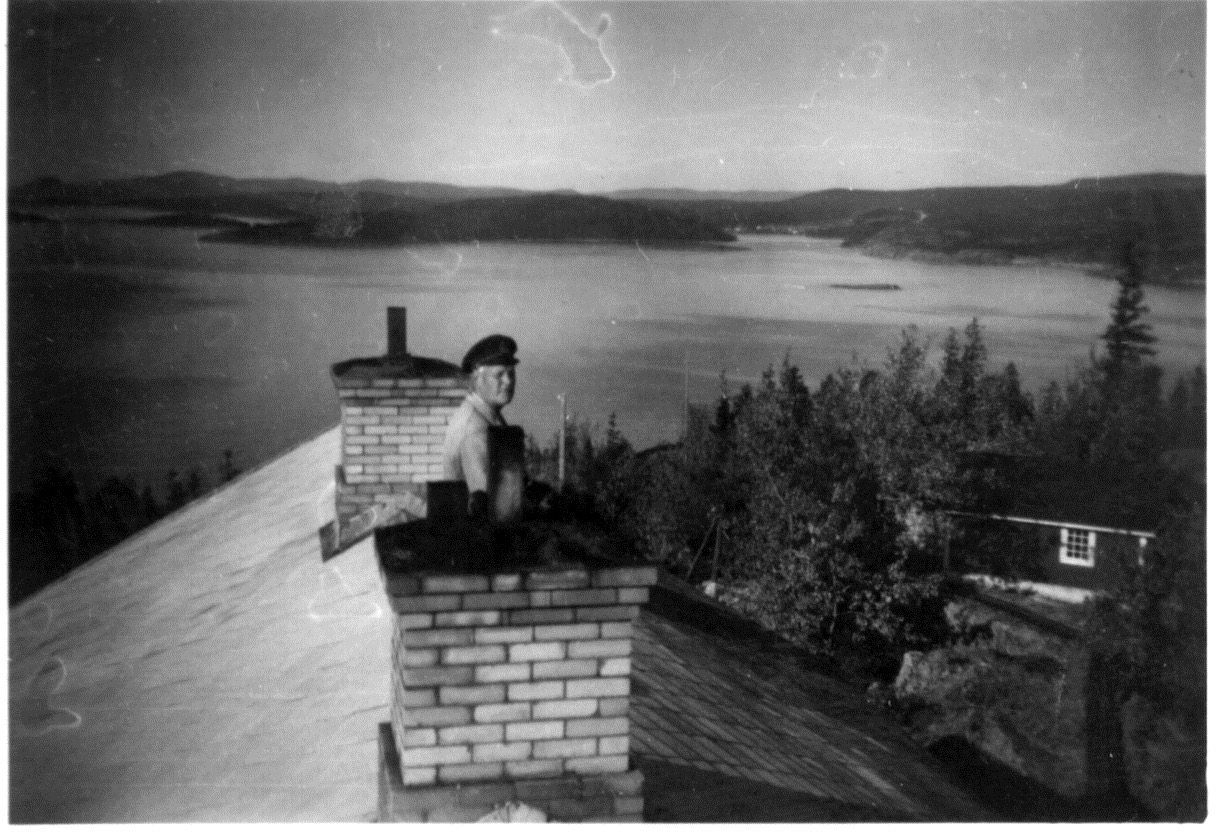

Knut on the roof.

Highly placed lighthouse master! Knut Jansson inspects the roof of the dwelling. The cable car’s engine house to the right in the picture. Behind it was grandmother Augusta’s tiny garden plot. Grandmother had a “green thumb.” Unfortunately there was no cultivable land on the barren rocky island.

Page 33 #

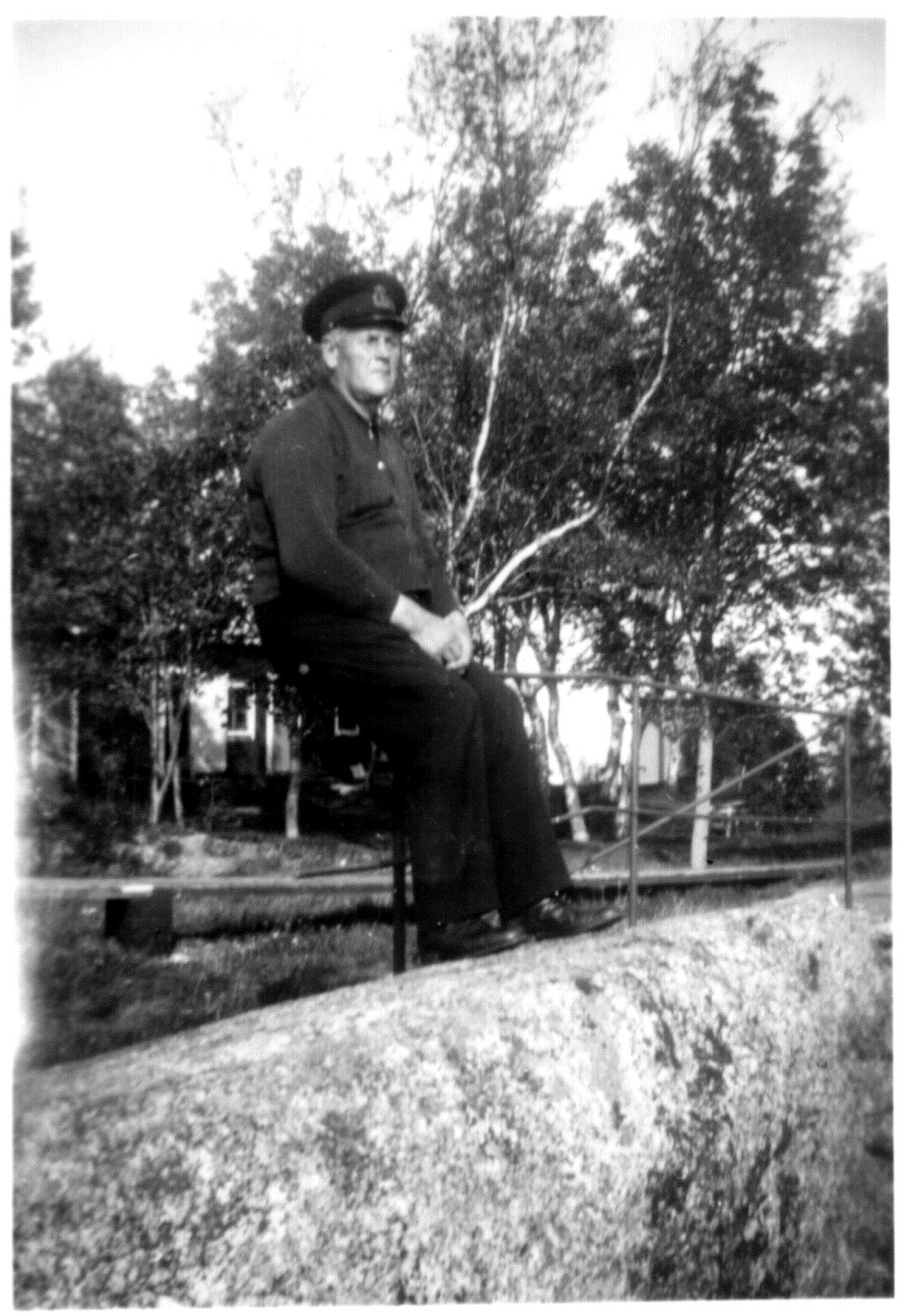

Last summer on Högbonden.

Nice picture of grandfather Knut. He sits gazing out over the sea. In the background you can see the outbuilding that is now a café. It’s grandfather’s last summer on the island before retirement and moving to the mainland. Government employees could receive pension at 60 years of age in those days. It’s an emotional moment that the camera has captured here. It probably felt bittersweet to leave the island after 26 years.

From Roslagen's Embrace — A family story from Högbonden